Dr. Margaret Fortune, Black in School coalition member and founder of Fortune Schools based in SacramentoRussell Stiger Jr. / Sacramento Observer

Dr. Margaret Fortune, Black in School coalition member and founder of Fortune Schools based in SacramentoRussell Stiger Jr. / Sacramento ObserverLate last week, a coalition of Black educators, legislators and students stood on the steps of the State Capitol to underscore the academic structures that have consistently underserved 80,000 Black students in California.

“We're tired of being invisible,” said Dr. Margaret Fortune, founder of Fortune Schools based in Sacramento. Fortune is one of many activists in the state who are part of the Black in School coalition.

Data from California’s current education funding model, called the Local Control Funding Formula, indicates that Black students have been academically behind for the last 10 years. The pandemic has only intensified this gap. Over the past several years, the Black in School coalition has voiced its concerns, pushing four different measures through the state legislature, only to have them fail.

The coalition says Governor Gavin Newsom’s 2023-24 education budget, which he said would account for the 80,000 Black students, misses the mark. At the Capitol event, Black educators and activists emphasized the failings of Newsom’s education policy, which is intended to circumvent race, but they say in reality bolsters damaging misconceptions and overlooks Black students in a system which is not built to serve them.

In 2013, California adopted the Local Control Funding Formula, or LCFF, to equitably distribute funds to schools and close the achievement gap for disadvantaged youth.

Dr. Ramona Bishop, Black in School coalition member and co-founder of Elite Public Schools in VallejoRussell Stiger Jr. / Sacramento Observer

Dr. Ramona Bishop, Black in School coalition member and co-founder of Elite Public Schools in VallejoRussell Stiger Jr. / Sacramento ObserverUsing the LCFF model, funding was allotted based on the number of students in classrooms. Additionally, each district could get a supplemental grant based on the number of vulnerable students in three high-needs subgroups: English learners, foster youth and a group comprised of low-income and unhoused youth. If more than 55% of a district’s students fall into these subgroups, the district qualifies for these additional monies.

After a decade, the data confirms that LCFF has not accomplished what it set out to do.

Dr. Ramona Bishop, a coalition member and co-founder of Elite Public Schools in Vallejo, has persisted in her fight for culturally inclusive education.

“Right at the beginning of [LCFF], Black advocates were saying, ‘Hey, what about the lowest performing group?’ We said that ten years ago,” she said.

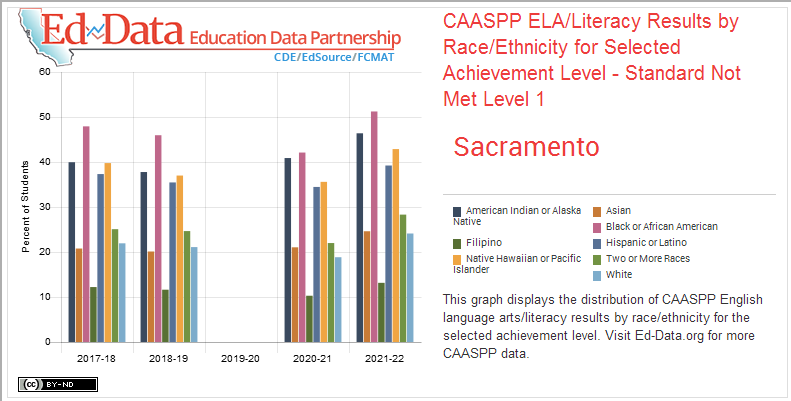

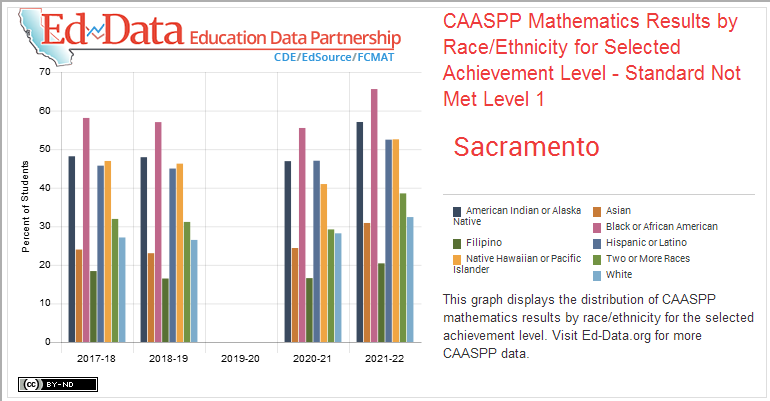

Statewide, almost 70% of Black students are not meeting English language standards and 84% are not meeting math standards. Between 2014-2022, in Sacramento, math and literacy rates have stagnated with nearly 50% of Black students meeting state standards — a staggering number that spotlights that Black students are lagging behind all their peers. In comparison, 75% of their white peers are meeting reading and math standards.

“California has not come up with a proxy for race,” said Fortune. “And this administration, in a misguided way, believes that proxy is income.”

Fortune added that Newsom’s education policy insinuates all underserved Black students are low-income and that the vehicle for closing the opportunity gap is by funding low-income schools.

Her fellow educator Bishop corroborated that such policy perpetuates harmful stereotypes and does not address the root of educational disparities.

“How can you assume that any one of them is poor? How can you assume that it is the case that their families do not want the best for them?” Bishop asked. “We’re going to say Black today.”

Debra Watkins, Black in School coalition member and founder of A Black Education Network in the San Francisco Bay AreaRussell Stiger Jr. / Sacramento Observer

Debra Watkins, Black in School coalition member and founder of A Black Education Network in the San Francisco Bay AreaRussell Stiger Jr. / Sacramento ObserverFortune and Bishop both suggested racial erasure is systemic in education. They point to Proposition 209, a 1996 amendment to the California state constitution, prohibiting the use of racial identifiers in education bills.

Debra Watkins, coalition member and founder of A Black Education Network in the San Francisco-Bay Area, said that race is an uncomfortable truth in education access.

“I have never met a teacher who got up in the morning and said, ‘How many Black and Brown children can I harm?’ I've never met a teacher like that ever,” said Watkins. “It's that unconscious bias.”

Tinsae Birhanu, a 17-year-old Cosumnes Oaks High School student, said she is no stranger to being encumbered by her race in the classroom.

“In AP U.S. History, people often stare at you when they talk about slavery. I feel like I'm in this alone,” she said.

Birhanu added she feels discouraged from pursuing subjects because of the way conversations are framed in the classroom.

Hannan Canada, President of Black Students of California United, confirmed this experience of Black students in Sacramento County. When discussing Black history and literature in the classroom, she said she worries about her responses and playing into stereotypes like the “persona of an angry Black woman.” She said that we can’t ignore race in school settings.

“How come whenever we talk about the subject of [being] Black, it always goes back to slavery and racism,” asked Canada. “What about our achievements? We learn so little about that. And when we have predominantly white teachers teaching those subjects, that's all we're taught.”

Hannan Canada, Cosumnes Oaks High student and President of Black Students of California UnitedRussell Stiger Jr. / Sacramento Observer

Hannan Canada, Cosumnes Oaks High student and President of Black Students of California UnitedRussell Stiger Jr. / Sacramento ObserverThree separate bills to amend the LCFF specifically for low-performing Black students have been authored in partnership with the coalition and all have failed to advance. The most recent — Assembly Bill 2774 — was filed as “inactive” after passing through both houses of the state legislature with bipartisan support.

The bill, authored by Assembly member Dr. Akilah Weber and backed by the Black in School coalition, attempted to add the low-performing subgroup to the LCFF, and as defined by Prop 209, avoided using any racial identifiers. This subgroup would have accounted for 80,000 Black students who are not included in the other subgroups, but require sustained funding support.

When that bill was tabled last year, after a closed door conversation with Newsom, the coalition was told that the 2023-24 education budget would provide one-time funding to address Black achievement.

“We believed that we would be included in those additional conversations to address the lowest performing group,” said Elite Public Schools’ Bishop. “However, we were not included in those conversations and therefore we're not sure who was at the table around expertise with regard to addressing the needs of Black students within schools.”

The Newsom administration’s education budget includes an equity multiplier which targets low-income schools and adds a $300 million fund to the LCFF. Coalition members Bishop, Fortune and Watkins all said that this approach is the opposite of what they are demanding.

“It feels very disrespectful,” said Watkins. “We had one singular purpose in mind, and that was to finally give the 80,000 black students, who are not being served under LCFF and have not been served for a decade, what they needed financially in their school systems in order to improve their educational outcomes.”

She said it was a blow to the many Black educators and students who have used data, lived experience and culturally-competent teaching practices to inform their legislative efforts.

Fortune concluded: “We're calling you out today, Governor Newsom, to say you must do better by Black students.”

Srishti Prabha is a Report For America corps member and Education Reporter in collaboration with The Sacramento Observer and CapRadio. Their focus is on K-12 education in Black communities.

Follow us for more stories like this

CapRadio provides a trusted source of news because of you. As a nonprofit organization, donations from people like you sustain the journalism that allows us to discover stories that are important to our audience. If you believe in what we do and support our mission, please donate today.

Donate Today