NPR | Staff

As Beethoven set about composing his Third Symphony, his hearing was failing and he felt certain his life was about to get worse. That it was born in a moment of despair may help explain why the finished work, for all its grandeur, is extremely odd — employing devices that are by turns aggressive and mundane, somber and practically danceable.

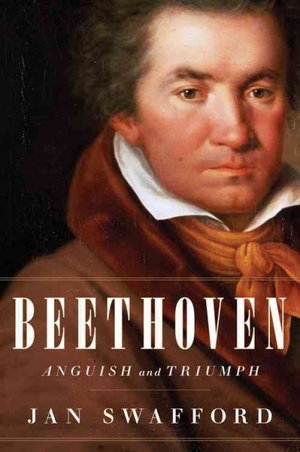

The piece also called the Eroica is one of many covered in Jan Swafford's massive new biography, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph. Swafford spoke with NPR's Arun Rath about the symphony and its composer; hear the radio version at the audio link and read an edited version of their conversation below.

The piece also called the Eroica is one of many covered in Jan Swafford's massive new biography, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph. Swafford spoke with NPR's Arun Rath about the symphony and its composer; hear the radio version at the audio link and read an edited version of their conversation below.

(And If there's anything you've always wanted to know about Beethoven, you'll have a chance to ask Jan Swafford. Check out his Reddit "Ask Me Anything" discussion with NPR Music's Tom Huizenga on Thursday Aug. 7 at 12 noon, ET.)

Arun Rath: I want to start off by getting right to the music. And we can go right to the start of the symphony because, right in the beginning, the Eroica is weird. It starts with Beethoven practically punching you in the face with those two big chords.

Jan Swafford: For the beginning of a symphony it's pretty aggressive; I don't know anything before it quite like it. And there are so many things in the first page that are strange and innovative for the time. In no symphony had the cellos ever taken the opening theme alone the way they do there.

And yet, people are used to hearing cellos play the melody now.

Beethoven really liberated the cello. In most classical symphonies the cellos are just sawing along with the basses, and Beethoven, more and more, gave them independent parts.

This title, the Eroica, refers to a hero, and the original hero he had in mind was Napoleon. Can you explain what Beethoven found heroic about Napoleon?

In those days, Napoleon was in the full glory of his power. There had never been anybody like him, who sort of raised himself from nobody, by his own bootstraps, to be the most powerful person in the world. And his reputation among liberals was as the man who was going to bring representative governments, rational governments and good laws to all of Europe: He was going to complete the French Revolution. And that's how Beethoven took him. He was exalting Napoleon, basically, as a benevolent despot.

And how do we hear this character, this kind of revolutionary character, reflected in the music?

The first movement is the most direct. As I said, I think it's a symbolic battle, but there's something very weird about it, which is that it's in 3/4.

It's more of a dancey meter.

It is — it has this sort of waltzy swing. The only explanation I can offer is that Beethoven wanted an abstraction of heroism, without military music. But it takes the rest of the symphony for the story to play out.

There is a march, but it's a funeral march.

Yeah, I mean, the logical thing: After the battle you bury the dead. There's a funeral march, which I think is an absolutely French Revolutionary-style, humanistic funeral march. It's not a hymn to god; it's a hymn to humanity. And it's so expressive and so tragic and so original, musically. There's a big horn fugue in the middle that, to me, is one of the greatest moments in music. That moment is one of the reasons I, and probably a lot of people, are musicians today.

To give some context here, as Beethoven is working on a third symphony, he's also confronting the worst thing you could think of happening to a musician: the loss of his hearing. Can you talk about what was going on with his hearing at that time?

We can kind of understand this in modern terms as the full weight of a disability hitting him in the face. In 1802, he finally had to face the fact that he really was going deaf, and he really was not going to be a composer-pianist anymore, but just a composer. And his health problems, which were chronic and miserable on top of the deafness, were probably not going to go away, and his life was going to be wretched, essentially. And he was right! It was, to a large extent, physically.

He wrote this letter, unmailed, to his brothers that we call the Heiligenstadt Testament, from the town he wrote it in. And it's half suicide note and half defiance, and finally saying, "I know it's going to be really terrible, the rest of my life, and I'm going to go deaf — but I'm going to stay alive for my art." He said, "I can't imagine leaving before I've done what I know I can do." And then, the Eroica came out — although I think he would have written the Eroica anyway. But from that point on, the next seven years were just beyond belief in his output.

And then, there's the finale. After a big flourish, we're introduced to a melody that's kind of lopey and dull, and kind of ugly.

The finale defines what a lot of critics at the time called "the bizarre." It's just incomprehensible, because it starts off with this kind of militaristic eruption, and then it goes into this very simple bass line — just absolutely nothing. But as I say in the book, it's a nothing on which anything can be built.

It begins in this tone of very light dance music and gradually becomes more and more heroic. I think, in terms of the program, the finale is what the hero brings to the world: the ideal society which respects freedom, and in which people like a Napoleon and a Beethoven can rise as high as their own abilities can take them.

Do you think it's fair to say the Eroica changed music?

Absolutely. It showed how massive and ambitious and historic a symphony could be. And it was a revelation of individual personality in music, a kind of powerful personality. He was an enormously powerful individual, and from the Eroica on, every piece of his — every ambitious piece, anyway — was an extraordinary individual.

Read An Excerpt