The denouement of a 35-year-drama takes place Thursday at the U.S. attorney's office in Manhattan. And I trust that my father, virtuoso violinist Roman Totenberg, who died three years ago, will be watching from somewhere.

For decades he played his beloved Stradivarius violin all over the world. And then one day, he turned around and it was gone. Stolen.

While he was greeting well-wishers after a concert, it was snatched from his office at the Longy School of Music in Cambridge, Mass.

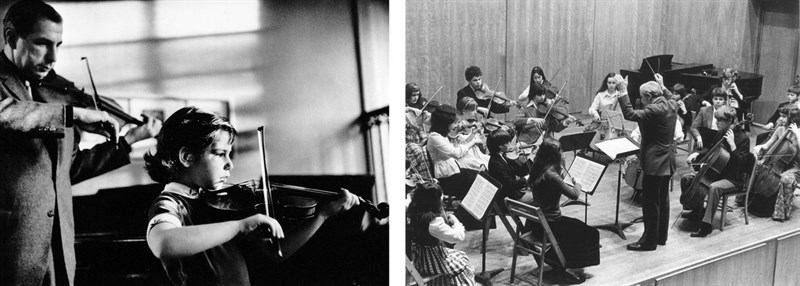

(Left) Roman Totenberg practices with his daughter, Amy. (Right) Totenberg conducts a student orchestra. He had a long career teaching at places such as Boston University and the Tanglewood Music Center, and he was director of the Longy School of Music. Courtesy of the Totenberg family / NPR

It was a crushing loss for my father. As he put it, he had lost his "musical partner of 38 years." And when he would ultimately buy a Guarneri violin from the same period as the Stradivarius, he had to rework the fingering of his entire repertoire for the new instrument.

My father would dream of opening his violin case and seeing the Strad there again, but he never lay eyes on it again. He died in 2012, but the Stradivarius lived on — somewhere.

Then, on the last day in June, I got a call from FBI Special Agent Christopher McKeogh.

"We believe that the FBI has recovered your father's stolen violin," he said.

As the reality of his message washed over me, I had a hard time actually believing it. I called my sisters right away, and we were soon laughing and crying on the phone.

I would love to tell you some bizarre story of the violin's travels through the underworld, but the true story is much more mundane, even pathetic.

My father had always suspected who had stolen the violin — a young aspiring violinist named Phillip Johnson, who was largely unknown to my father but had been seen outside my dad's office around the time the violin was stolen. Soon thereafter, Johnson's ex-girlfriend went to my parents and told them she was quite sure Johnson had taken it. Law enforcement officials believed, however, that was not enough for a search warrant. My mother was so frustrated that she famously would ask friends if they knew anyone in the mob willing to break into an apartment and search for the violin.

Phillip Johnson eventually moved to California, had an undistinguished musical career and died of cancer at age 58, a year before my father died at the age of 101.

Fast forward another four years. Johnson's ex-wife and her boyfriend are cleaning house and they come across a locked violin case that her former husband had left to her, with a combination lock on it. They broke the lock and opened the case to find a violin with a label inside that said it was made in 1734 by the most famous violin maker of all time — Antonio Stradivari.

A musician friend put her in touch with violin maker and appraiser Phillip Injeian in Pittsburgh.

"Of course I hear almost every day people telling me that they found a Stradivarius in the attic," Injeian says.

That's because, while there are only about 550 Stradivarius violins in existence today, there are thousands and thousands of violins that have a "Stradivarius" label stamped inside them — some of them good copies, and some just cheap imitations. So Injeian suggested the ex-wife send him photographs rather than waste a trip to the East Coast.

The photos she sent looked "so remarkably good," he says that he went to the Violin Iconography of Antonio Stradivari, the compilation of all Stradivarius instruments known to exist, and looked at instruments made in 1734. There he saw that a famous violin belonging to Roman Totenberg had been stolen and never recovered. It was known as the "Ames Stradivarius," after violinist George Ames, who performed on it in the late 1800s.

Soon the appraiser and the ex-wife agreed to meet in New York. And on June 26, Injeian went to her hotel.

"I opened the case and looked at the instrument," and, "checked it out for over a half hour before I said anything," he recalls.

"And I said these words, 'Well, I've got good news for you, and I've got bad news for you,' " Injeian says. " 'The good news is that this is a Stradivarius. The bad news it was stolen 35, 36 years ago from Roman Totenberg.' "

Injeian also told her he had to report the discovery to law enforcement authorities right away.

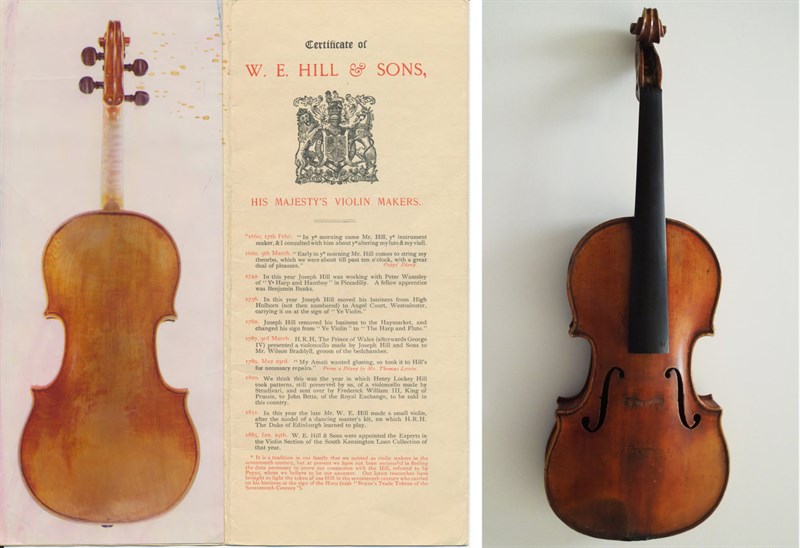

(Left) Documentation of the Ames-Stradivarius. (Right) An image of the Stradivarius when the FBI collected it last month. Courtesy of the Totenberg family / Courtesy of FBI New York

Within two hours Special Agents McKeogh and John Iannuzzi from the FBI's Art Theft team were at the hotel.

"It's rare in our business that we have the opportunity for one-stop shopping," McKeogh says, noting that the stolen violin, the person who possessed it and the expert appraiser were all there. "Having those three things in the same place was very rare, but good for us."

En route to the hotel, McKeogh and his partner had pulled up on their cell phones photos of the Ames Stradivarius taken before it was stolen, along with its precise measurements to the millimeter. Now, appraiser Injeian measured, calling out the numbers, and they matched exactly.

That was a Friday. McKeogh remembers the following Monday "because I can say that I have probably never been so excited to come to work as I was [that] morning, simply because I couldn't wait to see the instrument again." He knew, as well, that further authentication of the violin was necessary, and it came, amazingly, in that first call to me.

"You mentioned little pieces of pearl on the tuning pegs, and I went back to the violin as I was speaking to you and noticed those features, which is very unique," McKeogh says. A third confirmation would come later from another appraiser.

So, the mystery was solved. All these years, the violin had been in the same guilty hands.

Appraiser Injeian says Johnson had tried to preserve the instrument himself but knowing that any reputable restorer or dealer would recognize it, he had not had the violin properly maintained by the expert craftsmen who do this kind of work.

"It's a real miracle that it didn't take any major hits or cracks or anything of that nature," Injeian says.

And so on Thursday, at the U.S. attorney's office in New York, there will be a formal ceremony turning the violin over to the Totenberg sisters — Nina, Jill, and Amy — under an agreement filed in federal court. (You can hear more on the ceremony on Thursday's All Things Considered, and we will update this post after the event in New York.)

"It's nice to return something of great value to a family or a country or an institution," says U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara, adding, that these "are moments of celebration that we don't have that often here."

Of course, Stradivarius owners are really just guardians of these great artistic instruments. We will sell the Ames Strad — now perhaps the Ames-Totenberg Stradivarius. We will make sure it is in the hands of another virtuoso violinist. And once again, the beautiful, brilliant and throaty voice of that long-stilled violin will thrill audiences in concert halls around the world.

Stolen with my father's violin was a bow made by the Stradivarius of bow makers, Francois Tourte. Special Agent McKeogh is "hopeful" that in light of this story, someone with information about the bow will come forward. In addition, there is another stolen Stradivarius out there, the Davidoff-Morini Strad, taken from the apartment of violinist Erica Morini in 1995. Anyone with information about either the bow or the violin is asked to contact the New York office of the FBI at 212-384-5000 and to ask for Agent McKeogh.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.

View this story on npr.org